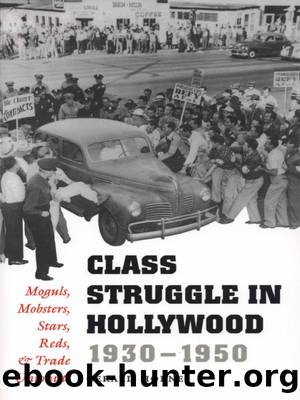

Class Struggle in Hollywood, 1930-1950 by Gerald Horne

Author:Gerald Horne

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: -

Publisher: University of Texas Press

Published: 2013-10-23T16:00:00+00:00

By mid-March 1945 the studios had a weekly payroll of $2.5 million and 130 films on the shelves—a nine-month supply. This was not necessarily the most fortuitous moment for a studio strike.

Still, shortly after the strike was launched, “business offices were in a snarl” and “without electricians to operate generators, no current was available to shoot scenes on prepared sets.” Disney, Monogram, and some independents were unaffected by the strike because they had bargained with Local 1421.72 Columbia, RKO, Universal, Warner Bros., and Fox were affected most severely, with MGM and Paramount right behind.

The Communists were no less displeased with the strike. Sorrell and CSU had “fallen into a trap” they contended. Hutcheson, the “reactionary Republican labor boss of the Carpenters Union and close ally of John L. Lewis,” was a culprit, along with the moguls, they argued; Sorrell’s actions were deemed “highly individualistic and irresponsible.” The Communists claimed that “production” was “virtually unimpaired” by the strike.73 The strike was antidemocratic, they claimed, since CSU as a whole never voted. It simply had backed the “unilateral action” of six hundred Local 1421 members who walked out: “that is the total number of workers in the movie industry who have officially voted to strike.”74

Organizations believed to be close to the party agreed with the Reds. As late as September 1945 the Hollywood Democratic Committee was reviewing its earlier refusal to take a position on the strike.75

The Reds’ criticisms were not going unanswered. At a mass meeting at Hollywood’s American Legion Stadium, Edward Boyle—a set decorator—assailed the Screen Writers Guild for not backing the strike, and added that the group’s failure was due to the influence of “leftwingers.” These “leftwingers” and “capitalists” made “strange bedfellows,” it was said.76

The Communists did blast the producers who canceled union contracts and discharged workers who walked out: “[T]his amounts to a virtual lockout…. Its obvious intent is to initiate jurisdictional war…. This has been a cardinal aim of the producers from the very beginning,” and CSU had fallen willingly into this trap.77 Still, the Communists could not have been pleased when their presumed ideological polar opposite—the Los Angeles Times—agreed with their viewpoint, declaring that the strike “takes the blue ribbon for asininity in wartime labor relations disputes.”78

The Communist critique was echoed among some studio unions. The Screen Publicists Guild, the Teamsters, and the Screen Story Analysts were among those that voted initially not to back the strike.79 Yet CSU had struck a nerve among workers with its audacious action. The climate was redolent with criticisms of big capital and its role in plunging Germany, Japan, and other nations into war; inevitably, these comments made U.S. workers more skeptical about big capital’s intentions in the United States itself. Thus, “picket lines [did] grow” during the first two weeks of the strike. Warner Bros. was the “hottest spot,” not only because it had been targeted by CSU but also because some members of IATSE Local 44 at this studio were sympathetic to CSU.80 As Variety reported, “[D]espite a

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1684)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1608)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1539)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1443)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1402)

Tip Top by Bill James(1400)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1358)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1342)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1337)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1322)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1297)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1290)

F*cking History by The Captain(1283)

American Dreams by Unknown(1271)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1248)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1244)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1199)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1163)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1110)